(Video below) A coworker recently discovered that her very tall bamboo was very invasive. When she recently bought the house, she was told it was that non-invasive kind. Right. It had sent roots under a shed and around the sewer pipe. It was coming up everywhere. Eradicating it would mean digging deep down to remove every bit of root.

(Video below) A coworker recently discovered that her very tall bamboo was very invasive. When she recently bought the house, she was told it was that non-invasive kind. Right. It had sent roots under a shed and around the sewer pipe. It was coming up everywhere. Eradicating it would mean digging deep down to remove every bit of root.

“Or I could move,” she said. “And get away from it.”

She won’t be the first to express that sentiment. Nor the last. Here in the Pacific Northwest, everything grows- with a vengeance. If you amend your soil, give plants some summer water, then voila, they grow bigger than the plant list says and take over the earth. If blackberry or ivy is on your property, you can’t turn your back without fearing a coup.

Even the house is habitat to a Pacific slope flycatcher.

I’ve been planting for 17 years. I buy bareroot plants at the annual Conservation District sale. Then there are plants that I propagate. My neighbor gives me plants. Plants volunteer on their own, too.

For years, I felt like I had to save every seed, every live stake, and plant it somewhere. There weren’t enough barriers to keep out my neighbor’s cows. There weren’t enough plants for nesting.

Goatsbeard, salal and bleeding heart in bloom. There is a path in there somewhere.

Then the balance started to tip. I had starts coming up everywhere. Plants needed dividing. I started noticing hawthorns and cherry trees growing wild along the roadway.

The volunteer red dogwood reached 20 feet into the air, and 30 feet across. A volunteer willow erupted into an exploding green fountain. Cherry branches drooped over the gate, dark red leaves shading the entry. Pacific ninebark branches drooped low over the driveway. The weeping cedar in front of the house grabs me as I try to clean the roof. Oceanspray sprouts in the gravel path, and wood sorrel carpets the garden along with some groundcover the previous owner planted. The rose that beavers mowed down last year springs back as a lush hedge.

I started to be grateful when something died, or the squirrels or rabbits ate it.The giant cherry trees my predecessor planted tipped over. Oh, darn. The Italian prune plum that grew to 20 feet in two years blew down. Oh, darn. I even gave away hundreds of plants the last couple years to get rid of pots and thin things.

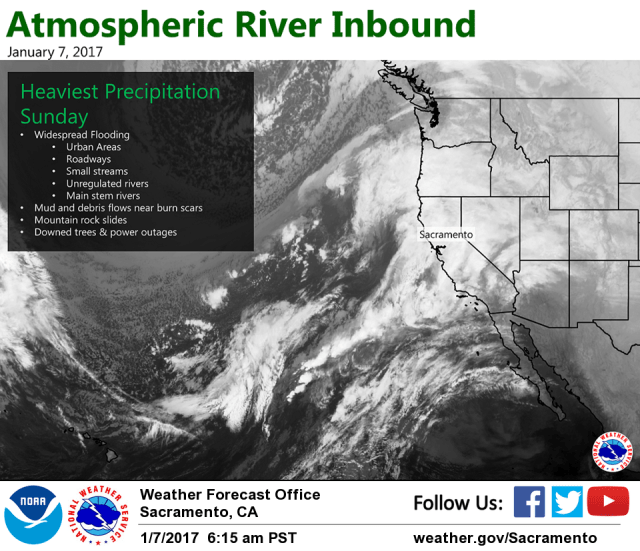

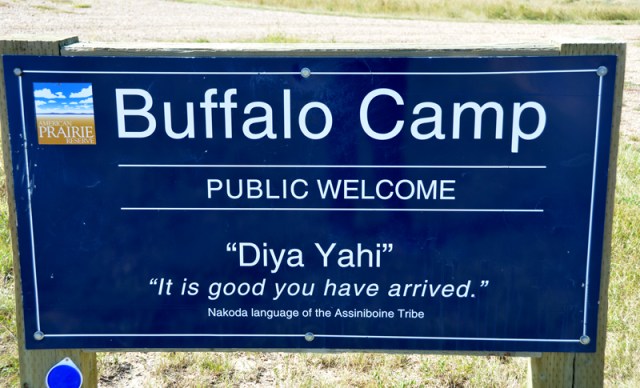

This winter, we got 4 feet of rain between October and March. The spring wore on, cool and wet. When I came home from a trip to the Montana prairie after two weeks of nice weather, the contrast between the dry, open prairie and my jungle was overwhelming. I felt like I was entering a tight leafy tunnel as I drove through the gate.

Wildlife thrives in this florid abundance. American goldfinches show up at the feeders in flocks, and disappear into thickets to hidden nests. A robin angrily attacks its reflection in one window after another for weeks. Squirrels race after each other up and down trees. A tangle of garter snakes unwinds from the crack between the concrete pad and barn floor. A red-tail hawk hunts from owl perches and weasels roam the fence rails in search of eggs and small birds.

Wildlife thrives in this florid abundance. American goldfinches show up at the feeders in flocks, and disappear into thickets to hidden nests. A robin angrily attacks its reflection in one window after another for weeks. Squirrels race after each other up and down trees. A tangle of garter snakes unwinds from the crack between the concrete pad and barn floor. A red-tail hawk hunts from owl perches and weasels roam the fence rails in search of eggs and small birds.

I won’t complain or move, because I signed up for this. And wielding a loppers beats checking the latest news in this historic crazy time. Dragging cuttings into slash piles and digging out weeds wears me down so that I sleep at night. Diligent effort opens corridors and paths, and gives shrubs and trees a fresh start.

As I work, kingfishers rattle warnings on the river where they have burrows, robin parents escort a fledgling out to forage, bald eagles trill at a youngster testing its wings, hawks soar over the field. A towhee takes a stand on top of a cedar and a Pacific slope flycatcher sneaks insects to nestlings tucked on top of the breaker box.

You know your habitat is complete when the vultures show up.

I could move, maybe to an apartment in the city, tidy and spare, with no yard work. I could join a gym and work out without getting sunburned, scratched by thorns or scalded by nettle. Or I could just stay here for awhile, where everything is simpler.

My remaining horse, and all the animals I’ve cared for here are also a reason for gratitude. I bought this house, located in such a perilous place, for my horses. Here I am now, down from four horses, two dogs, and two cats that came with the house. I one horse left, and he’s ageing and looking sore on one leg, and we can’t figure out what it is. I’m feeling the loss of my other horse, and this animal’s aching.

My remaining horse, and all the animals I’ve cared for here are also a reason for gratitude. I bought this house, located in such a perilous place, for my horses. Here I am now, down from four horses, two dogs, and two cats that came with the house. I one horse left, and he’s ageing and looking sore on one leg, and we can’t figure out what it is. I’m feeling the loss of my other horse, and this animal’s aching. This sanctuary is where I learned to heal the land and make a home for wildlife. Teaching other people what I learned over a decade of habitat restoration has made me a better communicator. Volunteering to give workshops lets me give something back to the world. My habitat project has helped my really see and understand wildlife. Animals have driven my art, my interests, my travel. The drive to restore even more every year keeps me moving, digging the earth, creating hedgerows and gardens and wild, tangled refuges.

This sanctuary is where I learned to heal the land and make a home for wildlife. Teaching other people what I learned over a decade of habitat restoration has made me a better communicator. Volunteering to give workshops lets me give something back to the world. My habitat project has helped my really see and understand wildlife. Animals have driven my art, my interests, my travel. The drive to restore even more every year keeps me moving, digging the earth, creating hedgerows and gardens and wild, tangled refuges. By the end of holiday break, I could see my house as far more than an object and investment again. I slowed down, puttered around, rearranged my space, reconnected enough to see it as more than a snapshot. Not racing by, on a schedule to get things done, as a place of chores and responsibilities and somewhere to rest between work days.

By the end of holiday break, I could see my house as far more than an object and investment again. I slowed down, puttered around, rearranged my space, reconnected enough to see it as more than a snapshot. Not racing by, on a schedule to get things done, as a place of chores and responsibilities and somewhere to rest between work days.

After the tour, we walk the trails, but it is getting hot now, with the sun out. The guide has said the sun shines more than it should in the Cloud Forests. “Climate change,” he tells us. “Sun will destroy the forest. It needs clouds, and mist, and cool.”

After the tour, we walk the trails, but it is getting hot now, with the sun out. The guide has said the sun shines more than it should in the Cloud Forests. “Climate change,” he tells us. “Sun will destroy the forest. It needs clouds, and mist, and cool.”

The upside of the drive was that we weren’t lost, and we saw one cause of decline of the resplendent quetzal, a charismatic bird everyone going to Monteverde Cloud Forest wants to see: a fragmented travel corridor between the mountains and the sea. Cattle ranches have denuded forest, leaving flying quetzals vulnerable to winged predators.

The upside of the drive was that we weren’t lost, and we saw one cause of decline of the resplendent quetzal, a charismatic bird everyone going to Monteverde Cloud Forest wants to see: a fragmented travel corridor between the mountains and the sea. Cattle ranches have denuded forest, leaving flying quetzals vulnerable to winged predators.

Thus my first view into the complex, interconnected world of the rainforest: an environment where any creature that plows the soil and recycles organic important is absolutely critical. Even a soldierly group of ants with a labyrinthine underground world.

Thus my first view into the complex, interconnected world of the rainforest: an environment where any creature that plows the soil and recycles organic important is absolutely critical. Even a soldierly group of ants with a labyrinthine underground world.

Cabinas Capulin was really our jumping off point to Monteverde and Santa Elena Cloud Forest Reserves, which I’ll cover in the next post. Suffice to say, it is an inexpensive place to stay, and a coworker recommended it when we couldn’t get into the

Cabinas Capulin was really our jumping off point to Monteverde and Santa Elena Cloud Forest Reserves, which I’ll cover in the next post. Suffice to say, it is an inexpensive place to stay, and a coworker recommended it when we couldn’t get into the

It’s cold. A thick layer of sparkly white frosting coats the tent like a muffin. I’d say the temperature is somewhere in the 20’s. It’s fall, so I expected this. I’m swaddled in synthetic puffy fabric and fleece, with rain jacket and pants to keep the slightest breeze from stealing heat. I brush most of the frost off the tent and then make coffee and read maps.

It’s cold. A thick layer of sparkly white frosting coats the tent like a muffin. I’d say the temperature is somewhere in the 20’s. It’s fall, so I expected this. I’m swaddled in synthetic puffy fabric and fleece, with rain jacket and pants to keep the slightest breeze from stealing heat. I brush most of the frost off the tent and then make coffee and read maps.

It won’t be easy, mostly because of people, past as well as present. I pass signs on the road protesting the Reserve. Ranchers worry about their way of life, though farm radio news indicates the economy and ranch debt is more threatening than conservation. People have introduced diseases like sylvatic plague that kills prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets alike. And we all know what weeds are like: psychotically clingy stalkers that reappear at every turn no matter how you try to ditch them.

It won’t be easy, mostly because of people, past as well as present. I pass signs on the road protesting the Reserve. Ranchers worry about their way of life, though farm radio news indicates the economy and ranch debt is more threatening than conservation. People have introduced diseases like sylvatic plague that kills prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets alike. And we all know what weeds are like: psychotically clingy stalkers that reappear at every turn no matter how you try to ditch them.

Finally, after setting up my temporary abode, I could stretch my legs walking out to the prairie dog town across the creek. I could watch the prairie sunset and moonrise and curl up well-insulated in my sleeping bag, ready to start exploring the next day.

Finally, after setting up my temporary abode, I could stretch my legs walking out to the prairie dog town across the creek. I could watch the prairie sunset and moonrise and curl up well-insulated in my sleeping bag, ready to start exploring the next day.