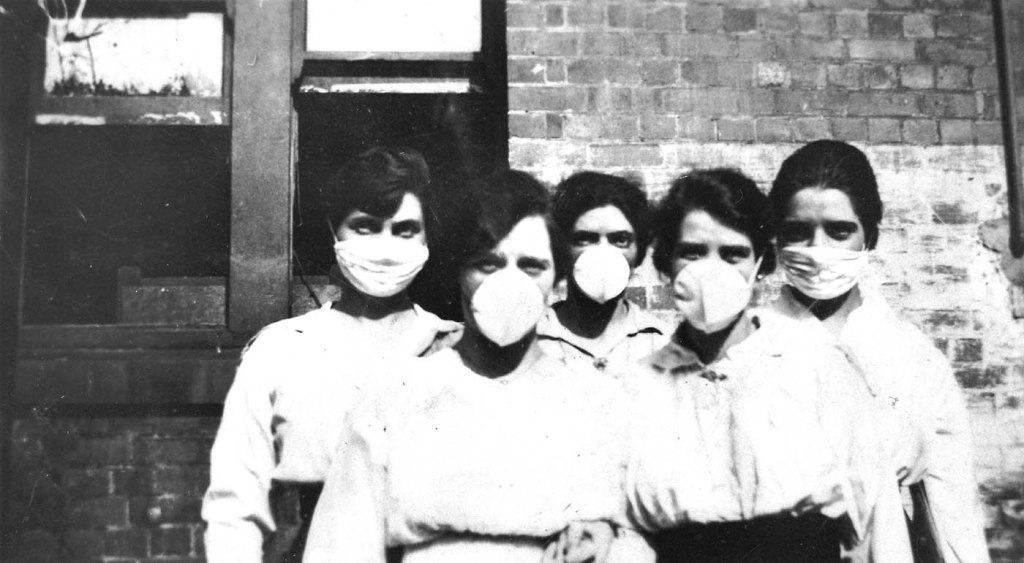

We all know things about ourselves that we keep inside. Those are things we hope don’t appear on the surface, don’t break the facade. We are trained to spend our lifetime keeping the mask in place, avoiding a slip. The lucky ones can’t wear a mask because it feels too suffocating or uncomfortable. They move through life as themselves, sometimes suffering, but always authentic.

And then the rest of the us stare in horror from behind our masks and call them odd or defective.

Behind my facade is an old pickup that has never worked quite right. It was supposed to be new, but it had a few flaws at the factory that get more out of kilter with time. The brakes have always been soft, the clutch pedal has to be pushed to the floor to change gears, and the steering is a bit sloppy. Now, as it gets older, stains, chips, noises, and rust are accummulating.

But the oddest thing about this old pickup is that it is driven by animals. I say animals broadly, referring to pretty much anything that is non-human and not a microorganism. I have a distinct fascination with microorganisms, too, like the slime molds that may make more cohesive communities in times of stress than humans can pull off lately.

Slime molds are “no more than a bag of amoebae encased in a thin slime sheath… Yet they manage to have various behaviors that are equal to those of animals who possess muscles and nerves with ganglia — that is, simple brains.” John Bonner

https://www.princeton.edu/news/2010/01/21/sultan-slime-biologist-continues-be-fascinated-organisms-after-nearly-70-years

It’s not about favoring something that provides me with unconditional devotion. Animals simply make more sense to me than people, and I get them. They fit into natural history and geologic time, surviving and evolving to adapt to the world around them.

Humans, on the other hand, don’t make sense: we barreled into modern times as a a seemingly self-destructive species that somehow overtook and destroyed nature, and perhaps ourselves in the long run. We spend more energy resenting, oppressing, and killing each other than actually surviving and thriving. We’ve deliberately driven the car over the cliff this time, believing with incredible hubris that we can transform it into a flying vehicle as we plummet into the canyon.

I finally had to admit that there is no room for another person in this car. I knew at a young age I would be a terrible parent, but I’ve learned I’m a terrible partner and friend as well. The few people who know me well get confused because I’m good with kids and I will rush into any wreckage or burning building to help people in need.

But that’s different from putting all the talons, paws, tentacles, and hooves in the back seat and letting a human being sit in the passenger seat- or heaven forbid, the driver’s seat.

I’m sure there is a name for this- we created clinical names for every shade of human, in a mix of catholic guilt and corporate control that views us all as vaguely defective and in need of a tidy box and a fix.

Figure this one out, if you will. I’ll give you a few hints: I was this way before my parents divorced or some of my siblings went wayward, before my mother died. I was this way from toddler-hood, hiding guinea pigs in the closet, breeding parakeets, bringing live and dead animals home from the park, drawing animals as a latch-key apartment kid in a city of over 3 million people.

The best people in my life probably know I’m a funky old jalopy. No one should care. The stuff society cares about- getting an education, holding down a job, paying bills and taxes, obeying the law: I’ve got that covered. Checked the boxes. I’ve kept the old pickup between the lines on the road, under the speed limit, although there have been many detours and interesting stops along the way.

Stranded

The emergence of an epidemic in my area has forced me to park at home for an indeterminate amount of time. A submicroscopic particle is bringing the world to its knees. Humans are being forced to accept that nature still exists, and we are subject to ancient laws. The current chaos and breakdown arose because we’re frantically trying to keep the mask in place, pretend we’re in control, and stave off the inevitable.

Stranded at home, I am being forced to take off my mask where no one is looking, and face reality: the passenger seat is empty of life, and I am not coping well.

Since Larkey left, suddenly and brutally, I have been trying to rebuild home and habits. My commute is too long and I travel too much to bring on any horse or dog or cat. I didn’t want to burden a pet with the requirement to be anchor for me but sit home alone all day and then get boarded when I hit the road.

I didn’t really figure it out, though I tried. I get distracted, volunteer whenever anyone asks, occupy myself with big projects,and travel. I have never sat still without a reason. It’s much easier to pack the old pickup and head to the hinterlands to see wild animals and greet the occasional pet or livestock I meet along the way.

My idea was that I would fill the pickup again, only with wildlife. Wild creatures are my roomies: I’ve been building habitat forever. I travel to see wildlife. It makes sense. But you have to switch gears into neutral, park the truck, and take the time to open the door and let things crawl, swim, fly, and climb in. Since Lark left broken in the back of a rendering truck, I’ve never even tried to push the tricky clutch pedal down far enough to let that happen.

I needed to sit alone in the truck and think about all of this for awhile. Once and for all, take the mask off and not care if everyone found me defective. But I never stopped thinking, never put the pickup in park to make a change.

Maybe stranded is a good thing. An opportunity.

As I sit here working, I’m fascinated by my own magical kingdom, even the little I can see and hear from my office window as I work. Big dark wings swoop by, a different bird call comes, the frogs sing, a tail slaps indignantly on the river, a moth-like creature hovers by the tree outside.

Maybe there is hope to reconnect with this place once again, to stop and open the door to let in the wild things that make more sense than we do.

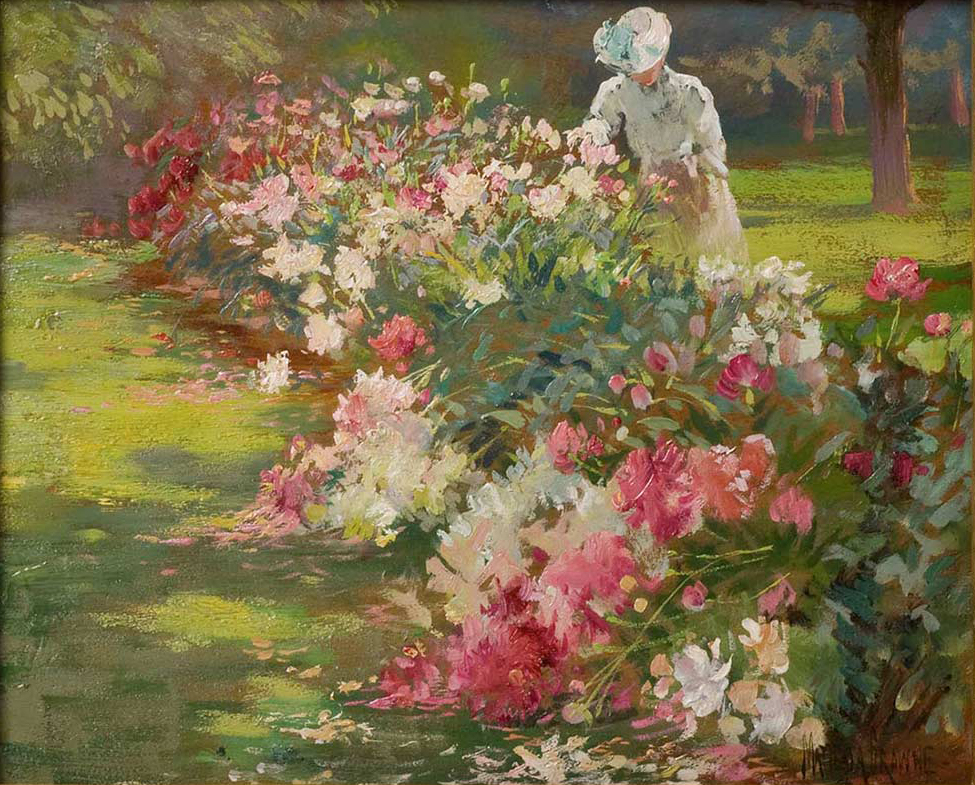

Monet purchased land across the road and created an engineered pond that artists and architects marvel at today. He worked with the local authorities on permission to divert a tributary of the Epte River, and then excavated a pond to hold it. Over the years, he created a bamboo-filled island, winding paths, and installed a bridge, and spread cultivated water lilies across the surface. Monet described the ethereal result in paintings still beloved today.

Monet purchased land across the road and created an engineered pond that artists and architects marvel at today. He worked with the local authorities on permission to divert a tributary of the Epte River, and then excavated a pond to hold it. Over the years, he created a bamboo-filled island, winding paths, and installed a bridge, and spread cultivated water lilies across the surface. Monet described the ethereal result in paintings still beloved today. Monet’s artistic efforts extended to the house, where vibrantly colored rooms housed collections of Japanese prints, Monet’s art, and art by friends of his. The shimmering yellow dining room hosted his extended family for meals. The Blue Salon housed his cherished Japanese prints, inspiration for his own art.

Monet’s artistic efforts extended to the house, where vibrantly colored rooms housed collections of Japanese prints, Monet’s art, and art by friends of his. The shimmering yellow dining room hosted his extended family for meals. The Blue Salon housed his cherished Japanese prints, inspiration for his own art.

The garden became a place where he could exorcise bad moods and dispel dark clouds. While he endured dark moods and raging self-doubt, the family would tiptoe around the house and eat silently. When Monet returned to garden work, everyone knew the dark period would lift.

The garden became a place where he could exorcise bad moods and dispel dark clouds. While he endured dark moods and raging self-doubt, the family would tiptoe around the house and eat silently. When Monet returned to garden work, everyone knew the dark period would lift.

How many of those people mistakenly see the ghostly gardener as a gentle, quiet man is not clear. The Acadèmie in its literature makes it clear that this garden is a work of art created by the hands of a haunted man who lived through historic times.

How many of those people mistakenly see the ghostly gardener as a gentle, quiet man is not clear. The Acadèmie in its literature makes it clear that this garden is a work of art created by the hands of a haunted man who lived through historic times.

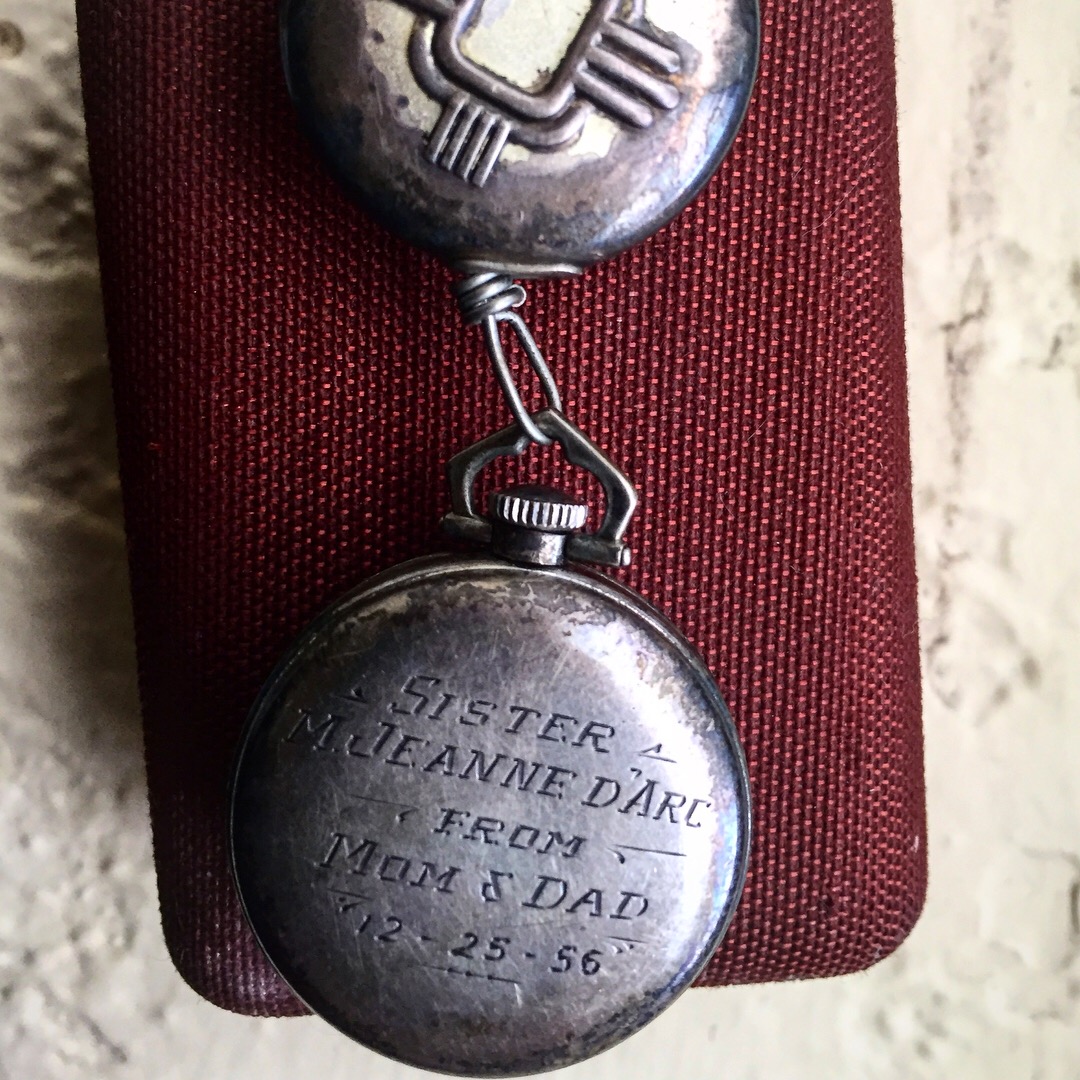

As part of becoming one with God, Catholic novitiates assume a new name, after a saint. At

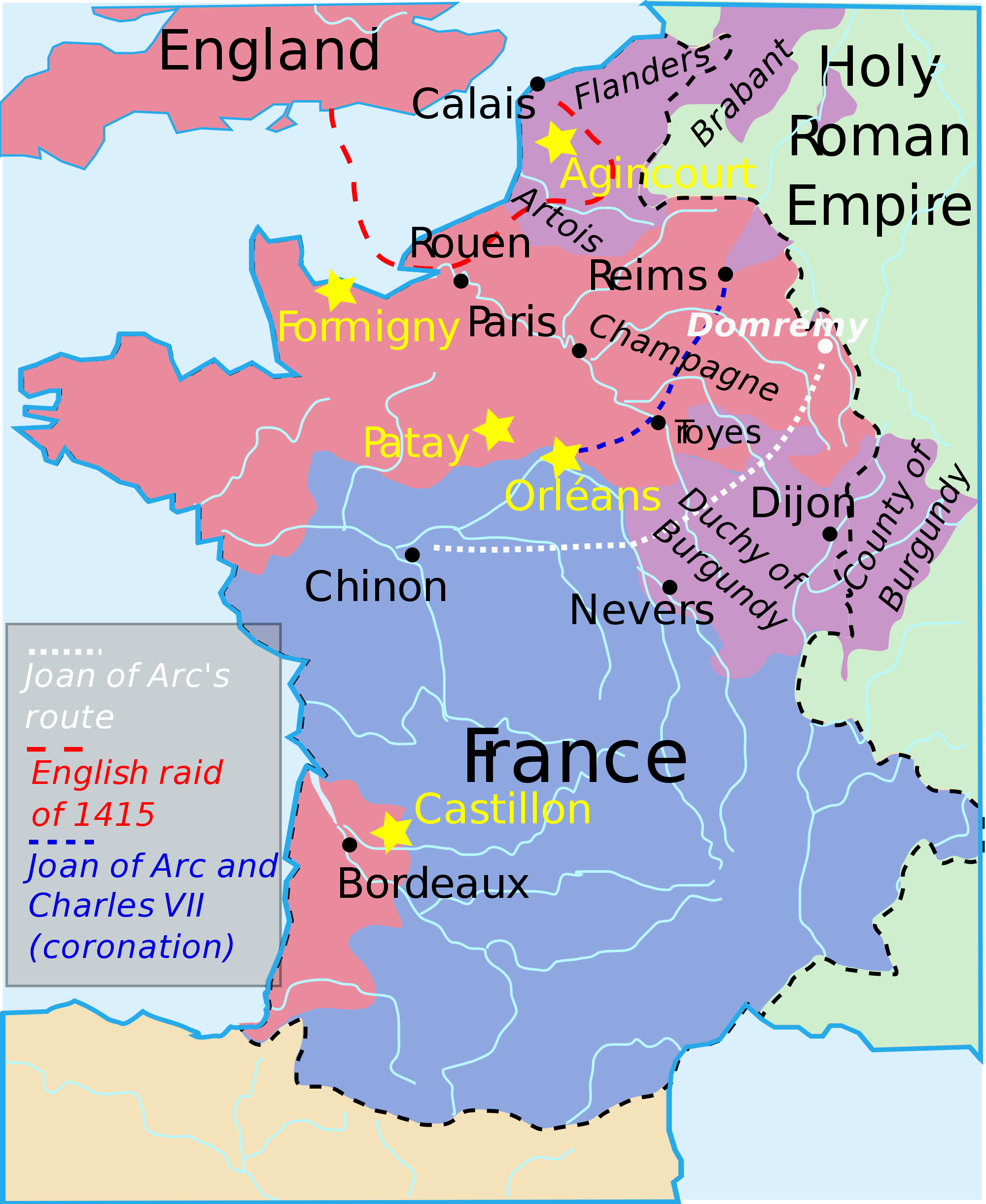

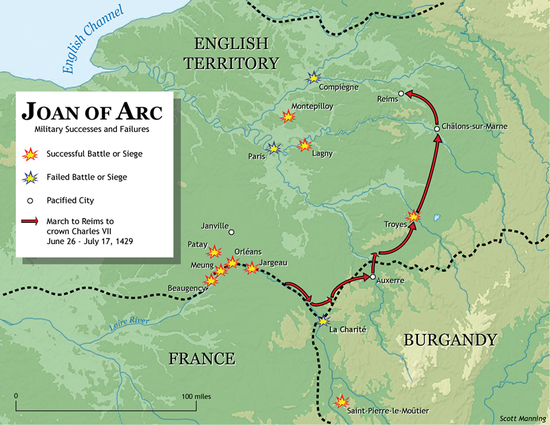

As part of becoming one with God, Catholic novitiates assume a new name, after a saint. At  It is a mystery why my mother took this name. She seemed too rational to identify with a fierce young woman who changed the course of history for France. Joan of Arc experienced visions and voices of saints and transformed herself into a teenaged warrior fighting for her country and king.

It is a mystery why my mother took this name. She seemed too rational to identify with a fierce young woman who changed the course of history for France. Joan of Arc experienced visions and voices of saints and transformed herself into a teenaged warrior fighting for her country and king.

![IMG_2089[1]](https://silversnagstudio.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/img_20891.jpg?w=300) I am reimagining the barn space because I won’t replace my horses. I work too far from my home to acclimate and train a new horse. They are herd animals, so more than one is better. I can’t be sure I’ll be around for the entire life of a couple young horses, and it isn’t easy to find a new home for equines.

I am reimagining the barn space because I won’t replace my horses. I work too far from my home to acclimate and train a new horse. They are herd animals, so more than one is better. I can’t be sure I’ll be around for the entire life of a couple young horses, and it isn’t easy to find a new home for equines. So I planted flowers in Larkey’s hay bins, to honor him and to soften the memory of what happened in the outside paddock. When the barn swallows are done nesting in September, I will clean his stall, repaint, and turn the space into an outdoor painting studio for the warm months. Maybe then his spirit will come back and keep me company.

So I planted flowers in Larkey’s hay bins, to honor him and to soften the memory of what happened in the outside paddock. When the barn swallows are done nesting in September, I will clean his stall, repaint, and turn the space into an outdoor painting studio for the warm months. Maybe then his spirit will come back and keep me company.

I count my blessings. I am lucky to have been tested young and learned how to adapt. I am resilient, and have the ability and resources to recreate. As the world gets darker and narrower, many find themselves trapped. I am not, at least right now. The terrible memory of Larkey’s death still sneaks up on me, but I am not an anguished parent adrift in a strange country with no idea where my children reside. I am not now in a war zone, wondering when the bombs will detonate.

I count my blessings. I am lucky to have been tested young and learned how to adapt. I am resilient, and have the ability and resources to recreate. As the world gets darker and narrower, many find themselves trapped. I am not, at least right now. The terrible memory of Larkey’s death still sneaks up on me, but I am not an anguished parent adrift in a strange country with no idea where my children reside. I am not now in a war zone, wondering when the bombs will detonate. And I have things to do. More stories to tell, artwork to create, images to capture. I need to get back into shape to backpack in the fall. I don’t know what the next year will hold for me, for the nation, for the world. But today and every day I can find something bright, and count myself fortunate for the time being.

And I have things to do. More stories to tell, artwork to create, images to capture. I need to get back into shape to backpack in the fall. I don’t know what the next year will hold for me, for the nation, for the world. But today and every day I can find something bright, and count myself fortunate for the time being. (Video below) A coworker recently discovered that her very tall bamboo was very invasive. When she recently bought the house, she was told it was that non-invasive kind. Right. It had sent roots under a shed and around the sewer pipe. It was coming up everywhere. Eradicating it would mean digging deep down to remove every bit of root.

(Video below) A coworker recently discovered that her very tall bamboo was very invasive. When she recently bought the house, she was told it was that non-invasive kind. Right. It had sent roots under a shed and around the sewer pipe. It was coming up everywhere. Eradicating it would mean digging deep down to remove every bit of root.

Wildlife thrives in this florid abundance. American goldfinches show up at the feeders in flocks, and disappear into thickets to hidden nests. A robin angrily attacks its reflection in one window after another for weeks. Squirrels race after each other up and down trees. A tangle of garter snakes unwinds from the crack between the concrete pad and barn floor. A red-tail hawk hunts from owl perches and weasels roam the fence rails in search of eggs and small birds.

Wildlife thrives in this florid abundance. American goldfinches show up at the feeders in flocks, and disappear into thickets to hidden nests. A robin angrily attacks its reflection in one window after another for weeks. Squirrels race after each other up and down trees. A tangle of garter snakes unwinds from the crack between the concrete pad and barn floor. A red-tail hawk hunts from owl perches and weasels roam the fence rails in search of eggs and small birds.

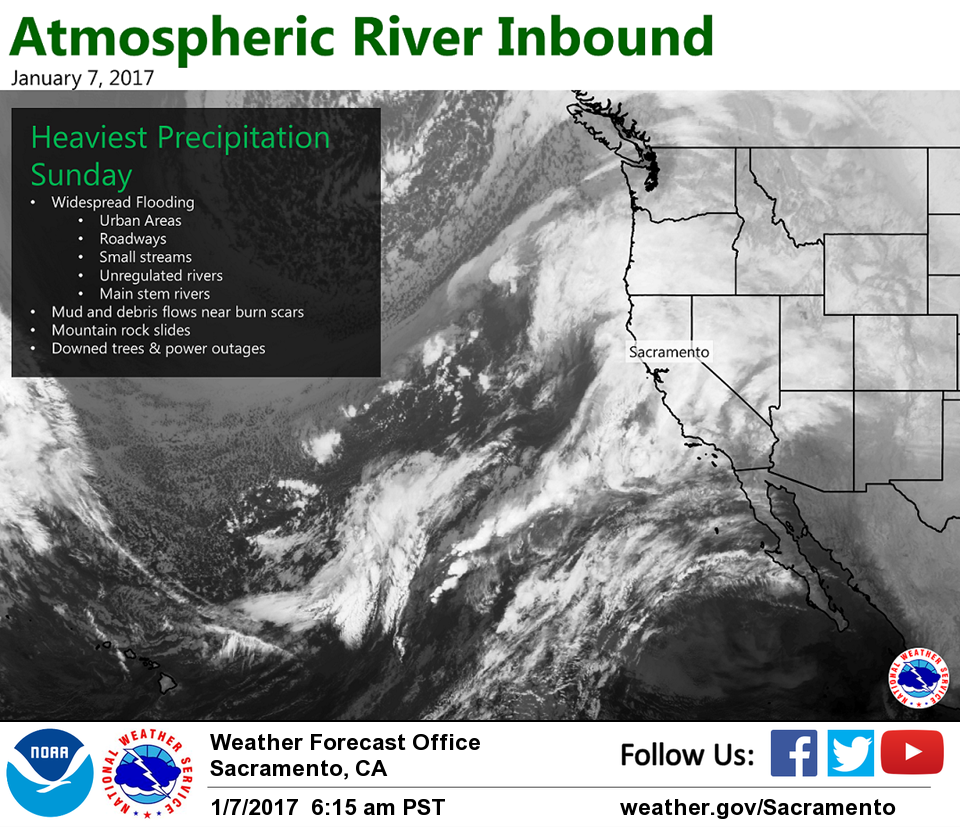

Heavy weather didn’t wash away the colors of skiers skimming trails in the Methow Valley. Occasional wet snow couldn’t dampen the teals and fuschias and yellows of modern outerwear. Petite teardrop packs rode neatly on people’s backs if they carried anything at all. Space age skis with optimized length and shape for easier turning painted the ground with a vibrant color palette.

Heavy weather didn’t wash away the colors of skiers skimming trails in the Methow Valley. Occasional wet snow couldn’t dampen the teals and fuschias and yellows of modern outerwear. Petite teardrop packs rode neatly on people’s backs if they carried anything at all. Space age skis with optimized length and shape for easier turning painted the ground with a vibrant color palette. And there I was, in my red and black, 23-year old North Face shell, everything else black, carrying a black and green, 20-year old Arcteryx pack. I wore my old Karhu half-metal edge, long, pointed skis. It’s not that I don’t own more modern gear. That gear hung neatly in closets, or slept quietly in a drawer.

And there I was, in my red and black, 23-year old North Face shell, everything else black, carrying a black and green, 20-year old Arcteryx pack. I wore my old Karhu half-metal edge, long, pointed skis. It’s not that I don’t own more modern gear. That gear hung neatly in closets, or slept quietly in a drawer. In a time when powerful people want to turn the world upside down, we’re weathering one piece of bad news after another, and nothing seems steady or logical, we turn to the familiar. My outdoor gear is my memento, my keepsake of a life lived as fully as I could considering I’m not a natural athlete, but naturally work too much.

In a time when powerful people want to turn the world upside down, we’re weathering one piece of bad news after another, and nothing seems steady or logical, we turn to the familiar. My outdoor gear is my memento, my keepsake of a life lived as fully as I could considering I’m not a natural athlete, but naturally work too much.

There are trails for fat bikes, with beefy snow tires. Trails for skate skiers and snowmobiles. Easy, medium, and hard trails. Trails that the neighbors decorate with crazy pink flamingos.

There are trails for fat bikes, with beefy snow tires. Trails for skate skiers and snowmobiles. Easy, medium, and hard trails. Trails that the neighbors decorate with crazy pink flamingos.

My remaining horse, and all the animals I’ve cared for here are also a reason for gratitude. I bought this house, located in such a perilous place, for my horses. Here I am now, down from four horses, two dogs, and two cats that came with the house. I one horse left, and he’s ageing and looking sore on one leg, and we can’t figure out what it is. I’m feeling the loss of my other horse, and this animal’s aching.

My remaining horse, and all the animals I’ve cared for here are also a reason for gratitude. I bought this house, located in such a perilous place, for my horses. Here I am now, down from four horses, two dogs, and two cats that came with the house. I one horse left, and he’s ageing and looking sore on one leg, and we can’t figure out what it is. I’m feeling the loss of my other horse, and this animal’s aching. This sanctuary is where I learned to heal the land and make a home for wildlife. Teaching other people what I learned over a decade of habitat restoration has made me a better communicator. Volunteering to give workshops lets me give something back to the world. My habitat project has helped my really see and understand wildlife. Animals have driven my art, my interests, my travel. The drive to restore even more every year keeps me moving, digging the earth, creating hedgerows and gardens and wild, tangled refuges.

This sanctuary is where I learned to heal the land and make a home for wildlife. Teaching other people what I learned over a decade of habitat restoration has made me a better communicator. Volunteering to give workshops lets me give something back to the world. My habitat project has helped my really see and understand wildlife. Animals have driven my art, my interests, my travel. The drive to restore even more every year keeps me moving, digging the earth, creating hedgerows and gardens and wild, tangled refuges. By the end of holiday break, I could see my house as far more than an object and investment again. I slowed down, puttered around, rearranged my space, reconnected enough to see it as more than a snapshot. Not racing by, on a schedule to get things done, as a place of chores and responsibilities and somewhere to rest between work days.

By the end of holiday break, I could see my house as far more than an object and investment again. I slowed down, puttered around, rearranged my space, reconnected enough to see it as more than a snapshot. Not racing by, on a schedule to get things done, as a place of chores and responsibilities and somewhere to rest between work days.

After the tour, we walk the trails, but it is getting hot now, with the sun out. The guide has said the sun shines more than it should in the Cloud Forests. “Climate change,” he tells us. “Sun will destroy the forest. It needs clouds, and mist, and cool.”

After the tour, we walk the trails, but it is getting hot now, with the sun out. The guide has said the sun shines more than it should in the Cloud Forests. “Climate change,” he tells us. “Sun will destroy the forest. It needs clouds, and mist, and cool.”