Our pets serve as silent, non-judgemental witnesses to our lives. They are memory-keepers who may hold more of our past and our secrets than our own families.

Times like these chase me into dream worlds, sanctuaries of whimsy and humor. Places far from hateful militia standoffs at bird refuges, bombastic presidential campaigns whipping a tornado of hate across the country, refugee crises, and terrorist bombings.

This year holds special reason to escape, besides the chaos in the news. 2016 is the 30th anniversary of the Challenger shuttle disaster, which I watched on television as a bright-eyed biology student in love with all science. The next day, drunk driving teenagers slammed into my mother’s pickup at 95 mph, plowing the truck into a granite wall and killing her. Three months later, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster struck.

For global reasons, not personal, this year is already starting to feel like 1986, a year where the world seemed to be collapsing in eternal flames. It doesn’t help that the news is disinterring the Challenger and Chernobyl tragedies, and family grief is likely to fly over email on January 29.

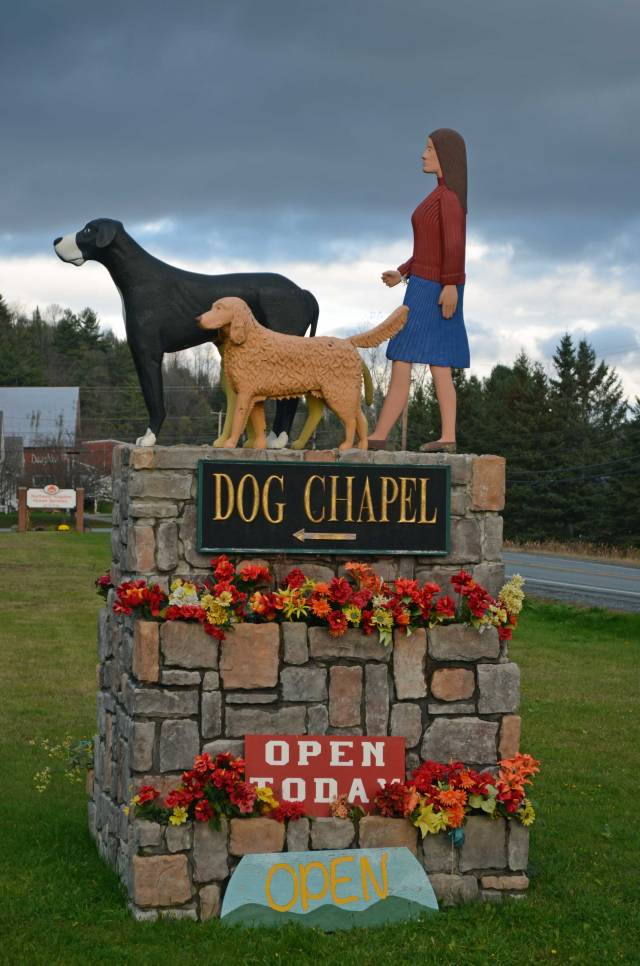

That’s when my mind flies to a sanctuary like Dog Mountain. I visited this unique Vermont attraction a couple years ago on a trip to see friends before they moved from their lifetime home. Dog Mountain is the gift of artist Stephen Huneck and his wife, Gwen, whose dogs were more spiritual companions than pets, allied in spirit like animals in the Inuit belief system. It was always a place for dogs to play: 150 acres of off-leash wonderland, with the dogs welcome in the buildings, too.

Mr. Huneck was a self-taught carver whose quirky, story-rich dog creations are housed in places like the Smithsonian Institute. After a life-threatening illness, he was inspired to create the Dog Chapel, where people could celebrate the memory of long-lost pets. He thought people might leave a few notes and memorials; today, the chapel is plastered from floor to ceiling with notes from people paying tribute to beloved pets.

The feeling in this chapel is strong enough that I, a rare weeper, felt that tell-tale throat tightening and moist eyes.

It’s not that Dog Mountain is a kitschy, sentimental place; in fact, it’s a reminder of the tragedy of feeling too much. Mr. Huneck took his own life after he was forced to lay off employees in the economic crisis, and Mrs. Huneck followed a few years later. Her brother, who continues managing the operation, suggests that depression and possible bipolar disorder may have contributed to their suicides.

It’s that poignant story that gets you when you stand in the chapel and marvel at the pews and stained glass windows. Our pets serve as silent, non-judgemental witnesses to our lives. They are memory-keepers that may hold more of our past and our secrets than our own families.

It’s that poignant story that gets you when you stand in the chapel and marvel at the pews and stained glass windows. Our pets serve as silent, non-judgemental witnesses to our lives. They are memory-keepers that may hold more of our past and our secrets than our own families.

For Stephen and Gwen Huneck, their dogs likely served as a balance between a dull, hopeless ache inside and hope for the future. Their dogs’ sensible and pragmatic but peculiar lives may have been an outward focus away from the Hunecks’ inner turmoil.

My horse Larkey reminds me of this as he gently protests my late rising Sunday morning, pulling on my sleeve with his lips (he has learned the hard way that biting is not a tolerated form of horse expression). The Oregon standoff and presidential race are dragging on and getting weirder and scarier, but this Sunday, Larkey reminds me in our mutually understood language that breakfast is the most important thing in the world.

Besides remaining a place for dogs to play freely, Dog Mountain captures the peaceful sanctuary that pets become in a our bumpy personal and global worlds. When we outlive pets. they take fragments of our lives with them forever. While they live, they save us and give us purpose in a thousand indescribable – and unquestioning- ways.

The short-eared owls aren’t yet rare, but we still stand breathless waiting for them to fly moth-like as they hunt at sundown. We listen for their raspy barks in flight, watch for them to land on a post, rootwad, or elderberry stem, then their heads to wither us with the piercing owl stare. I know they are reliable here at the Welts-Samish restoration area, overwintering before returning to northern breeding grounds.

The short-eared owls aren’t yet rare, but we still stand breathless waiting for them to fly moth-like as they hunt at sundown. We listen for their raspy barks in flight, watch for them to land on a post, rootwad, or elderberry stem, then their heads to wither us with the piercing owl stare. I know they are reliable here at the Welts-Samish restoration area, overwintering before returning to northern breeding grounds.